1.Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) remains one of the most challenging emergencies in intensive care, where managing potential complications such as seizures is critical. The Neurocritical Care Society (NCS) published new guidelines about seizure prophylaxis in non-traumatic ICH, in this article I tried to summarize those guidelines.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, seizure prophylaxis, antiseizure medications, intensive care, levetiracetam, phenytoin, ICH guidelines.

2.Scope of the Guidelines

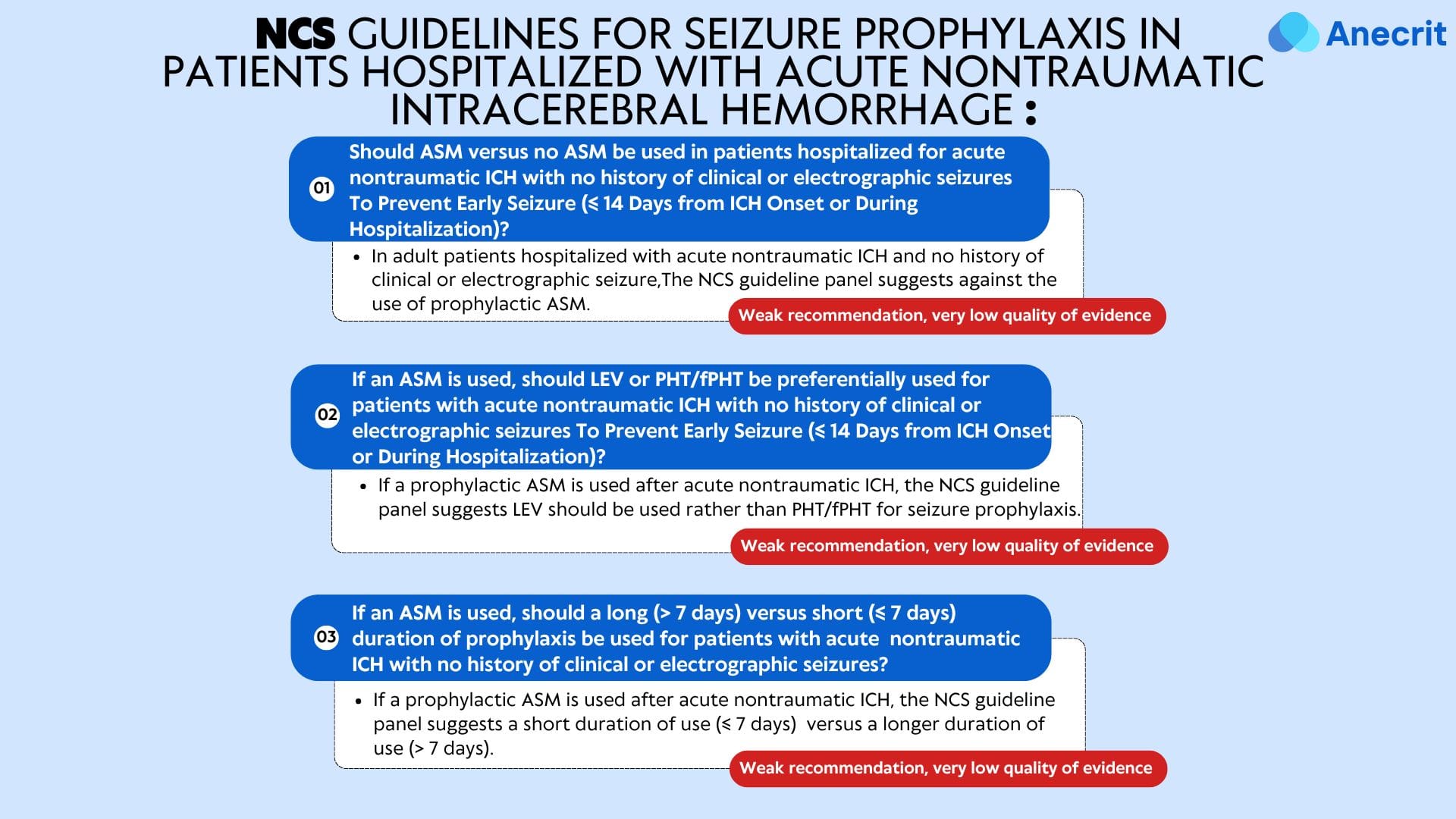

The recommendations tried to answer frequent questions that every clinician asks when taking care of patients with non-traumatic ICH :

- Prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis,

- Levetiracetam versus phenytoin/fosphenytoin,

- Long versus short duration of prophylaxis when indicated.

3.The Actual Guidelines

3.1. PICO 1:

Evidence Highlights:

Several questions were addressed in the body of the evidence for the guidelines:

- Is ASM effective for preventing late seizures defined as seizures occurring after 14 days from ICH onset or post-hospitalization?

- Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed no significant difference in late clinical seizures at 12 months (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.48–4.13, P=0.54, I²=0%).

- Is ASM associated with more adverse event rates compared to no ASM?

- Analysis of two RCTs and three non-RCTs indicated a significantly higher risk of any adverse event with ASM use (RR 1.95, 95% CI 1.03–3.68, P=0.04 I2 = 35%, P = 0.19 for heterogeneity). However, some studies reported no differences in behavioral side effects or delirium when comparing LEV to no ASM.

- Functional outcomes in ASM vs no ASM groups:

- Meta-analysis slightly favored the non-ASM group (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.35, P=0.03) despite significant heterogeneity (I²=65%, P=0.01 for heterogeneity).

- A pooled analysis of five studies showed no significant impact of ASM on 90-day adjusted modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.79–2.27, P=0.28, I²=79%, P<0.001 for heterogeneity).

- Is there a difference in mortality between ASM and no ASM groups of patients?

- overall, there was no difference in mortality (nor in the adjusted risk of death, in a pooled analysis) between the ASM vs no ASM groups based on a meta-analysis of six studies (two RCTs and four non-RCTs studies).

- cognitive outcomes in ASM vs no ASM groups:

- A retrospective study noted worse neuroQOL (Quality Of Life) cognitive function scores at 1 month in patients receiving LEV vs patients that did not receive ASM; however, these differences were not observed at 3 and 12 months.

3.2. PICO 2:

Evidence Highlights:

Several questions were addressed in the body of the evidence for the guidelines:

- Between LEV and PHT/fPHT, which one prevents better late seizures (>14 days from ICH onset or post-hospitalization)?

- No eligible studies were available to compare late seizure prevention between LEV and PHT/fPHT.

- Adverse events rate with LEV vs PHT/fPHT:

- Based on a meta-analysis of three non-RCT studies, no significant difference in adverse event rates was found between the two medications (pooled RR 2.62, 95% CI 0.74–9.26, P=0.14, I²=0%).

- Functional outcomes with LEV vs PHT/fPHT:

- One observational study (compared prophylaxis with PHT post ICH vs LEV prophylaxis/no ASM) reported that PHT was significantly associated with worse outcomes (mRS scores 4–6) at 90 days (adjusted OR 9.0, 95% CI 1.2–68.5, P=0.03). Note that some patients with underlying epilepsy were included in the PHT group.

3.3. PICO 3:

Evidence Highlights:

Several questions were addressed in the body of the evidence for the guidelines:

- Does long-duration prophylaxis prevent late seizures (defined as seizures occurring after 14 days from ICH onset or post-hospitalization)?

- two small RCTs found no difference in rates of late seizures at 12 months between ASM and placebo groups. One RCT evaluated LEV for 6 weeks vs placebo and the other VPA for one month vs placebo

- Is long-duration prophylaxis associated with more adverse event rates compared to short-duration prophylaxis?

- As stated in PICO 1, ASM is probably associated with more adverse event rates compared to no ASM, the authors concluded that an increased duration of exposure would increase the risk of adverse events.

- Functional Outcomes in Short‐Duration Versus Long‐Duration ASM

- The authors used the same meta-analysis stated in the response to the question of functional outcomes in ASM vs no ASM groups in PICO 1 (pooled RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.35, P = 0.03).

4.Limitations in the Evidence

Overall, the certainty of the evidence ranged from very low to low. This limitation underscores the pressing need for more robust, high-quality studies to better inform clinical decisions regarding seizure prophylaxis in ICH patients.

5.Authors' opinion:

5.1.PICO 1:

The decision to initiate ASM prophylaxis should be guided by a careful risk/benefit analysis. Tools such as the 2HELPS2B[2] or the CAVE[3] scores can assist in risk stratification:

- Medium - high Seizure Risk: Prophylactic ASM may be considered for medium seizure risk (12% risk, 2HELPS2B score = 1) or high seizure risk (>25% risk, 2HELPS2B score ≥2).

- Low Seizure Risk: ASM prophylaxis may be avoided in patients with a low seizure risk (<5% risk, 2HELPS2B score = 0).

In high-risk patients requiring continuous EEG—when not available—shorter duration routine EEG or limited montage rapid response EEG can be used, albeit with reduced sensitivity and specificity. When EEG is not available at all, the CAVE score (which is based solely on clinical features) may be employed.

The committee generally does not favor routine prophylactic ASM use in ICH patients. However, EEG findings may help identify a subset of patients who could benefit from targeted prophylactic therapy.

N.B: Most panel members reported use of continuous EEG monitoring for both deep and lobar ICH locations.

5.2.PICO 2:

LEV is increasingly preferred over PHT for ASM prophylaxis. The suggested dosing for LEV is as follows:

- For Creatinine Clearance >30 mL/min: 750–1,000 mg twice daily.

- For Augmented Renal Clearance ≥130 mL/min: Consider higher or more frequent dosing.

- For Creatinine Clearance ≤30 mL/min: Lower doses (e.g., 500 mg once or twice daily) are typically used.

N.B: Other molecules were also discussed.

5.3.PICO 3:

For patients without clinical seizures or high-risk EEG features, and if an ASM was used, the panel members reported that they would minimize the duration of ASM prophylaxis to ≤7 days.

However, the duration of secondary prophylaxis or primary prophylaxis when EEG demonstrates high-risk features, many panel members would opt to continue ASM post discharge taking into account the benefits/risks balance and reevaluate the patient in follow-up.

6.Conclusion

In summary, current evidence does not support routine prophylactic use of antiseizure medications in patients with acute non-traumatic ICH (in the absence of clinical or electrographic seizures). If seizure prophylaxis is prescribed, levetiracetam is preferred over phenytoin/fosphenytoin, and a short treatment duration (≤7 days) is suggested to reduce potential adverse events. These guidelines emphasize individualized patient assessment using risk stratification tools like the 2HELPS2B and CAVE scores. This balanced approach aims to optimize outcomes and ensure that interventions are both effective and safe for patients with ICH. Given the low quality of available evidence, further research is essential to refine these recommendations and improve seizure management in the intensive care setting.

The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended to replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider before making any decisions related to your health, particularly if you are experiencing any symptoms or have concerns about seizure management. The author and publisher assume no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content or for any outcomes resulting from the use of this information.

7.References:

- Guidelines for Seizure Prophylaxis in Patients Hospitalized with Nontraumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society.

- The 2HELPS2B Score calculator (Medscape).

- The CAVE Score for Predicting Late Seizures After Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

Comments ()